The log-0 problem: analysis strategies and options for choosing c in log(y + c)

I periodically find myself having long conversations with consultees about 0’s. Why? Well, the basic suite of statistical tools many of us learn first involves the normal distribution (for the errors). The log transformation tends to feature prominently for working with right-skewed data. Since log(0) returns -Infinity, a common first reaction is to use log(y + c) as the response in place of log(y), where c is some constant added to the y variable to get rid of the 0 values.

This isn’t necessarily an incorrect thing to do. However, I think it is important to step back and think about the study and those 0 values more before forging ahead with adding a constant to the data.

Some of the resources I’ve used over the years to hone my thinking on this topic are this thread on the R-sig-eco mailing list, this Cross Validated question and answers, and this blogpost on the Hyndsight blog.

I will explore the influence of c in log(y + c) via simulation later, so if that’s what you are interested in you can jump to that section.

Table of Contents

Thinking about 0 values

Without getting into too much detail, below are some of the things I consider when I have 0 as well as positive values in a response variable.

Discrete data

We have specific tools for working the discrete data. These distributions allow 0 values, so we can potentially avoid the issue all together.

Questions to ask yourself:

Are the data discrete counts?

If so, start out considering a discrete distribution like the negative binomial or Poisson instead of the normal distribution. If the count is for different unit areas or sampling times, you can use that “effort” variable as an offset.

Are the data proportions?

If the data are counted proportions, made by dividing a count by a total count, start with binomial-based models.

Models for discrete data can be extended as needed for a variety of situations (excessive 0 values, overdispersion, etc.). Sometimes things get too complicated and we may go back to normal-based tools but this is the exception, not the rule.

Continuous data

Positive, continuous data and 0 values are where I find things start to get sticky. The standard distributions that we have available to model positive, right-skewed data (log-normal, Gamma) don’t contain 0. (Note that when we do the transformation log(y) and then used normal-based statistical tools we are working with the log-normal distribution.)

Are the 0 values “true” 0’s?

Were the values unquestionably 0 (no ifs, ands, or buts!) or do you consider the 0’s to really represent some very small value? Are the 0’s caused by the way you sampled or your measurement tool?

This is important to consider, and the answer may affect how you proceed with the analysis and whether or not you think adding something and transforming is reasonable. There is a nice discussion of different kinds of 0’s in section 11.3.1 in Zuur et al. 2009.

What proportion of the data are 0?

If you have relatively few 0 values they won’t have a large influence on your inference and it may be easier to justify adding a constant to remove them.

Are the 0 values caused by censoring?

Censoring can occur when your measurement tool has a lower limit of detection and every measurement lower than that limit is assigned a value of 0. This is not uncommon when measuring stream chemistry, for example. There are specific models for censored data, like Tobit models.

Are the data continuous proportions?

The beta distribution can be used to model continuous proportions. However, the support of the beta distribution contains neither 0’s nor 1’s. Sheesh! You would need to either work with a zero-inflated/one-inflated beta or remap the variable to get rid of any 0’s and 1’s.

Do you have a point mass at 0 along with positive, continuous values?

The Tweedie distribution is one relatively new option that can work for this situation. For example, I’ve seen this work well for % plant cover measurements, which can often be a bear to work with since the measurements can go from 0 to above 100% and often contain many 0 values.

Another option I’ve used for “point mass plus positive” data is to think about these as two separate problems that answer different questions. One analysis can answer a question about the probability of presence and a second can be used to model the positive data only. This is a type of hurdle model, which I’ve seen more generally referred to as a mixture model.

Common choices of c

It may be that after all that hard thinking you end up on the option of adding a constant to shift your distribution away from 0 so you can proceed with a log transformation. In my own work I find this is most likely for cases where I consider the 0 values to be some minimal value (not true 0’s) and I have relatively few of them.

So what should this constant, c, be?

This choice isn’t minor, as the value you choose can change your results when your goal is estimation. The more 0 values you have the more likely the choice of c matters.

Some options:

Add 1. I think folks find this attractive because log(1) = 0. However, whether or not 1 is reasonable can depend on the distribution of your data.

Add half the minimum non-0 value. This is what I was taught to do in my statistics program, and I’ve heard of others with the same experience. As far as I know this is an unpublished recommendation.

Add the square of the first quartile divided by the third quartile. This recommendation reportedly comes from Stahel 2008; I have never verified this since I unfortunately can’t read German. 😜 This approach clearly is relevant only if the first quartile is greater than 0, so you must have fewer than 25% 0 values to use this option.

Load R packages

Let’s explore these different options for for one particular scenario via simulation. Here are the R packages I’m using today.

library(purrr) # v. 0.2.5

library(dplyr) # v. 0.7.6

library(broom) # v. 0.5.0

library(ggplot2) # v. 3.0.0

library(ggridges) # v. 0.5.0Generate log-normal data with 0 values

Since the log-normal distribution by definition has no 0 values, I found it wasn’t easy to simulate such data. When I was working on this several years ago I decided that one way to force 0 values was through rounding. This is not the most elegant solution, I’m sure, but I think it works to show how the choice of c can influence estimates.

I managed to do this by generating primarily negative data on the log scale and then exponentiating to the data scale. I make my x variable negative, and positively related to y.

The range of the y variable ends up with many small values with a few fairly large values.

I’ll set the seed, set the values of the parameters (intercept and slope), and generate my x first. I’m using a sample size of 50.

set.seed(16)

beta0 = 0 # intercept

beta1 = .75 # slope

# Sample size

n = 50

# Explanatory variable

x = runif(n, min = -7, max = 0)The response variable is calculated from the parameters, x, and the normally distributed random errors, exponentiating to get things on the appropriate scale. These data can be used in a log-normal model via a log transformation.

You can see the vast majority of the data are below 1, but none are exactly 0.

true_y = exp(beta0 + beta1*x + rnorm(n, mean = 0, sd = 2))

summary(true_y)# Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

# 0.0013 0.0146 0.0862 8.6561 0.4180 377.3488I force 0 values into the dataset by rounding the real data, true_y, to two decimal places.

y = round(true_y, digits = 2)

summary(y)# Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

# 0.000 0.010 0.085 8.656 0.420 377.350I fooled around a lot with the parameter values, x variables, and the residual errors to get 0’s in the rounded y most of the time. I wanted some 0 values but not too many, since the quartile method for c can only be used when there are less than 25% 0 values.

I tested my approach by repeating the process above a number of times. Here’s the number of 0 values for 100 iterations. Things look pretty good, although there are some instances where I get too many 0’s.

replicate(100, sum( round( exp(beta0 + beta1*runif(n, min = -7, max = 0) +

rnorm(n, mean = 0, sd = 2)), 2) == 0) ) [1] 6 8 8 4 2 4 7 6 4 7 6 10 9 8 7 4 6 10 8 5 8 6 4

[24] 12 7 10 3 7 7 9 3 6 9 7 4 12 5 11 11 9 4 8 5 6 16 6

[47] 7 7 7 7 12 10 8 9 7 10 13 6 5 12 9 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 15

[70] 4 8 10 5 7 9 6 9 9 4 4 8 0 7 4 9 9 8 6 9 6 10 5

[93] 7 3 9 9 7 9 3 13The four models to fit

You can see there is variation in the estimated slope, depending on what value I use for c, in the four different models I fit below.

Here’s the “true” model, fit to the data prior to rounding.

( true = lm(log(true_y) ~ x) )

Call:

lm(formula = log(true_y) ~ x)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) x

0.6751 0.9289Here’s a log(y + 1) model, fit to the rounded data.

( fit1 = lm(log(y + 1) ~ x) )

Call:

lm(formula = log(y + 1) ~ x)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) x

1.2269 0.2324Here’s the colloquial method of adding half the minimum non-0 value.

( fitc = lm(log(y + min(y[y>0])/2) ~ x) )

Call:

lm(formula = log(y + min(y[y > 0])/2) ~ x)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) x

0.6079 0.8348And the quartile method per Stahel 2008.

( fitq = lm(log(y + quantile(y, .25)^2/quantile(y, .75) ) ~ x) )

Call:

lm(formula = log(y + quantile(y, 0.25)^2/quantile(y, 0.75)) ~

x)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) x

0.8641 1.0558A function for fitting the models

I decided I want to fit these four models to the same data so I wanted to fit all four models within each call to my simulation function.

The beta0 and beta1 arguments of the functions can technically be changed, but I’m pretty tied into the values I chose for them since I had a difficult time getting enough (but not too many!) 0 values.

To make sure that I always had at least one 0 in the rounded y data but that less than 25% of the values were 0 so I included a while() loop. This is key for using the quartile method in this comparison.

The function returns a list of models. I give each model in the output list a name to help with organization when I start looking at results.

logy_0 = function(beta0 = 0, beta1 = .75, n) {

x = runif(n, -7, 0) # create expl var between -10 and 0

true_y = exp(beta0 + beta1*x + rnorm(n, 0, 2))

y = round(true_y, 2)

while( sum(y == 0 ) == 0 | sum(y == 0) > n/4) {

true_y = exp(beta0 + beta1*x + rnorm(n, 0, 2))

y = round(true_y, 2)

}

true = lm(log(true_y) ~ x)

fit1 = lm(log(y + 1) ~ x)

fitc = lm(log(y + min(y[y>0])/2) ~ x)

fitq = lm(log(y + quantile(y, .25)^2/quantile(y, .75) ) ~ x)

setNames(list(true, fit1, fitc, fitq),

c("True model", "Add 1", "Add 1/2 minimum > 0", "Quartile method") )

}Do I get the same values back as my manual work if I reset the seed? Yes! 🙌

set.seed(16)

logy_0(n = 50) $`True model`

Call:

lm(formula = log(true_y) ~ x)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) x

0.6751 0.9289

$`Add 1`

Call:

lm(formula = log(y + 1) ~ x)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) x

1.2269 0.2324

$`Add 1/2 minimum > 0`

Call:

lm(formula = log(y + min(y[y > 0])/2) ~ x)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) x

0.6079 0.8348

$`Quartile method`

Call:

lm(formula = log(y + quantile(y, 0.25)^2/quantile(y, 0.75)) ~

x)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) x

0.8641 1.0558Now I can simulate data and fit these models many times. I decided to do 1000 iterations today, resulting in a list of lists which I store in an object called models.

models = replicate(1000, logy_0(n = 50), simplify = FALSE)Extract the results

I can loop through the list of models and extract the output of interest. Today I’m interested in the estimated coefficients, with confidence intervals. I can extract this information using broom::tidy() for lm objects.

I use flatten() to turn models into a single big list instead of a list of lists. I loop via map_dfr(), so my result is a data.frame that contains the coefficients plus the c option used for the model based on the names I set in the function.

results = map_dfr(flatten(models),

~tidy(.x, conf.int = TRUE),

.id = "model")

head(results) # A tibble: 6 x 8

model term estimate std.error statistic p.value conf.low conf.high

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 True mod~ (Inter~ -0.912 0.543 -1.68 9.94e-2 -2.00e+0 0.179

2 True mod~ x 0.494 0.141 3.50 1.02e-3 2.10e-1 0.778

3 Add 1 (Inter~ 0.543 0.154 3.52 9.63e-4 2.33e-1 0.853

4 Add 1 x 0.0801 0.0402 1.99 5.18e-2 -6.46e-4 0.161

5 Add 1/2 ~ (Inter~ -0.908 0.461 -1.97 5.48e-2 -1.84e+0 0.0193

6 Add 1/2 ~ x 0.427 0.120 3.55 8.63e-4 1.85e-1 0.668I’m going to focus on only the slopes, so I’ll pull those out explicitly.

results_sl = filter(results, term == "x")Compare the options for c

So how does changing the values of c change the results? Does it matter what we add?

Summary stastics

First I’ll calculate a few summary statistics. Here is the median estimate of the slope for each c option and the confidence interval coverage (i.e., the proportion of times the confidence interval contained the true value of the slope; for a 95% confidence interval this should be 0.95).

results_sl %>%

group_by(model) %>%

summarise(med_estimate = median(estimate),

CI_coverage = mean(conf.low < .75 & .75 < conf.high) ) # A tibble: 4 x 3

model med_estimate CI_coverage

<chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Add 1 0.131 0

2 Add 1/2 minimum > 0 0.632 0.834

3 Quartile method 0.791 0.89

4 True model 0.750 0.941You can see right away that, as we’d expect, the actual model fit to the data prior to rounding does a good job. The confidence interval coverage is close to 0.95 and the median estimate is right at 0.75 (the true value).

The log(y + 1) models performed extremely poorly. The estimated slope is biased extremely low, on average. None of the 1000 models ever had the true slope in the confidence interval. 😮

The other two options performed better. The “Quartile method” gives estimates that are, on average, too high while the “Add 1/2 minimum > 0” options underestimates the slope. The confidence interval coverage is not great, but I suspect this is at least partially due to the way I artificially reduced the variance by rounding.

Graph the results

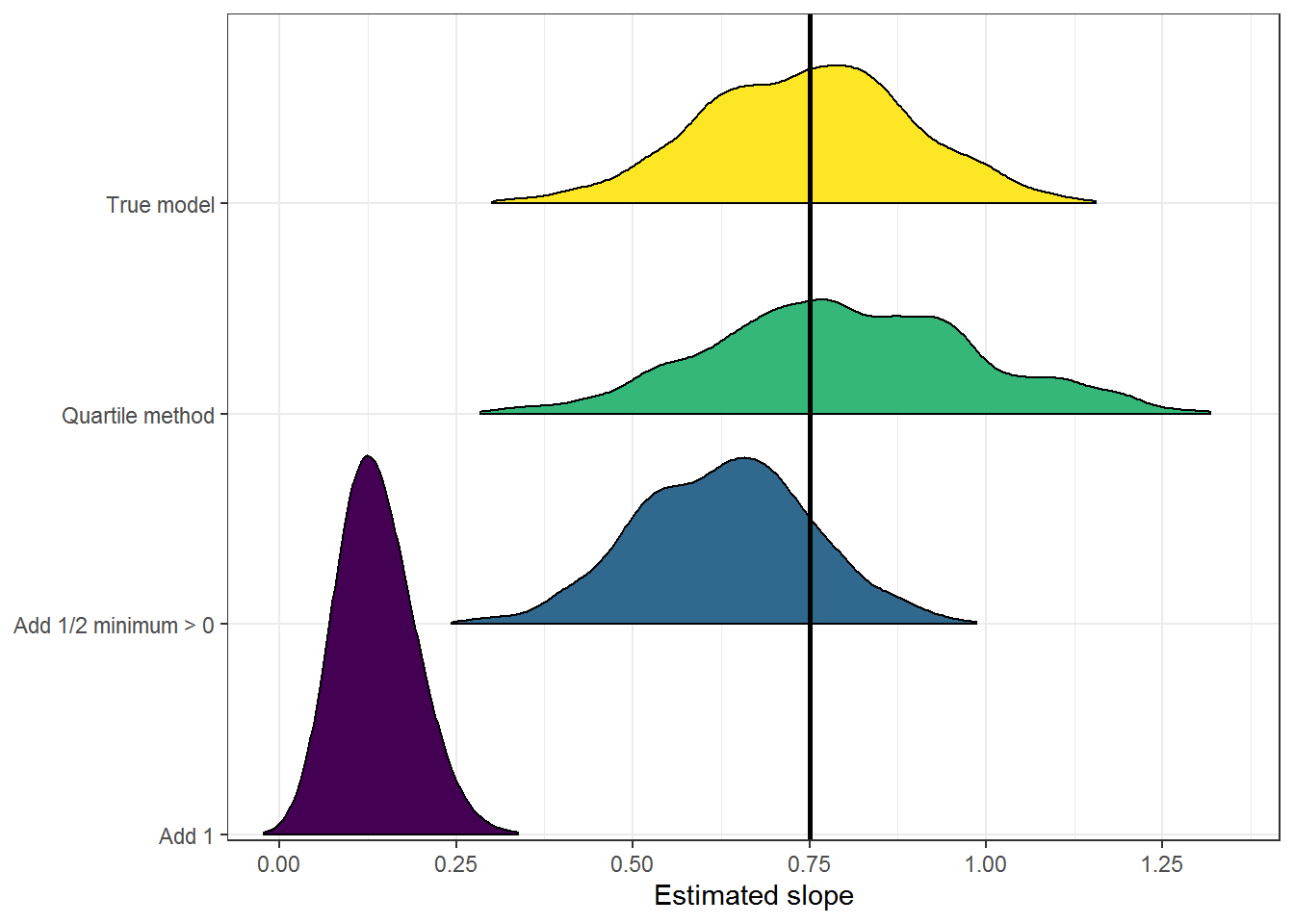

Here is a graph, using package ggridges to make ridge plots. This makes it easy to compare the distribution of slope estimates for each c option to the true model (shown at the top in yellow).

ggplot(results_sl, aes(x = estimate, y = model, fill = model) ) +

geom_density_ridges2(show.legend = FALSE, rel_min_height = 0.005) +

geom_vline(xintercept = .75, size = 1) +

scale_fill_viridis_d() +

theme_bw() +

scale_x_continuous(name = "Estimated slope",

expand = c(0.01, 0),

breaks = seq(0, 1.5, by = .25) ) +

scale_y_discrete(name = NULL, expand = expand_scale(mult = c(.01, .3) ) )

Again, the estimates from the “Add 1” models are clearly not useful here. The slope estimate are all biased very low.

The “Quartile method” has the widest distribution. It is long-tailed to the right compared to the distribution of slopes from the true model, which is why it can overestimate the slope.

And the “Add 1/2 minimum > 0” option tends to underestimate the slope. I’m curious that the distribution is also relatively narrow, and wonder if that has something to do with the way I simulated the 0 values via rounding.

Which option is best?

First, one of the main things I discovered is that my method for simulating positive, continuous data plus 0 values is a little kludgy. 😂 For the scenario I did simulate data for, though, adding 1 is clearly a very bad option if you want to get a reasonable estimate of the slope (which is generally my goal when I’m doing an analysis 😉).

Why did adding 1 perform so badly? Remember that when we do a log transformation we increase the space between values less than 1 on the original scale and decrease the space between values above 1. The data I created were primarily below 1, so by adding 1 to the data I totally changed the spacing of the data after log transformation. Using 1 as c is going to make the most sense if our minimum non-0 value is 1 or higher (at least for estimation).

The other two options both performed OK in this specific scenario. You may have noticed that statisticians generally dislike anti-conservative methods, so my guess is many (most?) statisticians would choose the conservative option (“Add 1/2 minimum > 0”) to be on the safe side. However, even if this pattern of over- and under-estimation holds more generally in other scenarios, the choice between these options should likely be based on the gravity of missing a relationship due to underestimation compared to the gravity of overstating a relationship rather than on purely statistical concerns.

Another avenue I think might be important to explore is how the number of 0 values in the distribution has an impact on the results. The choice between c options could depend on that. (Plus, of course, the “Quartile method” only works at all if fewer than 25% of the data are 0’s).

Just the code, please

Here’s the code without all the discussion. Copy and paste the code below or you can download an R script of uncommented code from here.

library(purrr) # v. 0.2.5

library(dplyr) # v. 0.7.6

library(broom) # v. 0.5.0

library(ggplot2) # v. 3.0.0

library(ggridges) # v. 0.5.0

set.seed(16)

beta0 = 0 # intercept

beta1 = .75 # slope

# Sample size

n = 50

# Explanatory variable

x = runif(n, min = -7, max = 0)

true_y = exp(beta0 + beta1*x + rnorm(n, mean = 0, sd = 2))

summary(true_y)

y = round(true_y, digits = 2)

summary(y)

replicate(100, sum( round( exp(beta0 + beta1*runif(n, min = -7, max = 0) +

rnorm(n, mean = 0, sd = 2)), 2) == 0) )

( true = lm(log(true_y) ~ x) )

( fit1 = lm(log(y + 1) ~ x) )

( fitc = lm(log(y + min(y[y>0])/2) ~ x) )

( fitq = lm(log(y + quantile(y, .25)^2/quantile(y, .75) ) ~ x) )

logy_0 = function(beta0 = 0, beta1 = .75, n) {

x = runif(n, -7, 0) # create expl var between -10 and 0

true_y = exp(beta0 + beta1*x + rnorm(n, 0, 2))

y = round(true_y, 2)

while( sum(y == 0 ) == 0 | sum(y == 0) > n/4) {

true_y = exp(beta0 + beta1*x + rnorm(n, 0, 2))

y = round(true_y, 2)

}

true = lm(log(true_y) ~ x)

fit1 = lm(log(y + 1) ~ x)

fitc = lm(log(y + min(y[y>0])/2) ~ x)

fitq = lm(log(y + quantile(y, .25)^2/quantile(y, .75) ) ~ x)

setNames(list(true, fit1, fitc, fitq),

c("True model", "Add 1", "Add 1/2 minimum > 0", "Quartile method") )

}

set.seed(16)

logy_0(n = 50)

models = replicate(1000, logy_0(n = 50), simplify = FALSE)

results = map_dfr(flatten(models),

~tidy(.x, conf.int = TRUE),

.id = "model")

head(results)

results_sl = filter(results, term == "x")

results_sl %>%

group_by(model) %>%

summarise(med_estimate = median(estimate),

CI_coverage = mean(conf.low < .75 & .75 < conf.high) )

ggplot(results_sl, aes(x = estimate, y = model, fill = model) ) +

geom_density_ridges2(show.legend = FALSE, rel_min_height = 0.005) +

geom_vline(xintercept = .75, size = 1) +

scale_fill_viridis_d() +

theme_bw() +

scale_x_continuous(name = "Estimated slope",

expand = c(0.01, 0),

breaks = seq(0, 1.5, by = .25) ) +

scale_y_discrete(name = NULL, expand = expand_scale(mult = c(.01, .3) ) )