Analysis essentials: Using the help page for a function in R

Since I tend to work with relatively new R users, I think a lot about what folks need to know when they are getting started. Learning how to get help tops my list of essential skills. Some of this involves learning about useful help forums like Stack Overflow and the RStudio Community. Some of this is about learning good search terms (this is a hard one!). And some of this is learning how to use the R documentation help pages.

While there are still exceptions, most often the help pages in R contain a bunch of useful information. Here I talk a little about what is generally in a help page for a function and what I focus on in each section.

Table of Contents

R help pages

Every time I use a function for a first time or reuse a function after some time has passed (like, 5 minutes in some cases 😜), I spend time looking at the R help page for that function. You can get to a help page in R by typing ?functionname into your Console and pressing Enter, where functionname is some R function you are using.

For example, if I wanted to take an average of some numbers with the mean() function, I would type ?mean at the > in the R Console and then press Enter. The help page opens up; if using RStudio this will default to open in the Help pane.

Help page structure

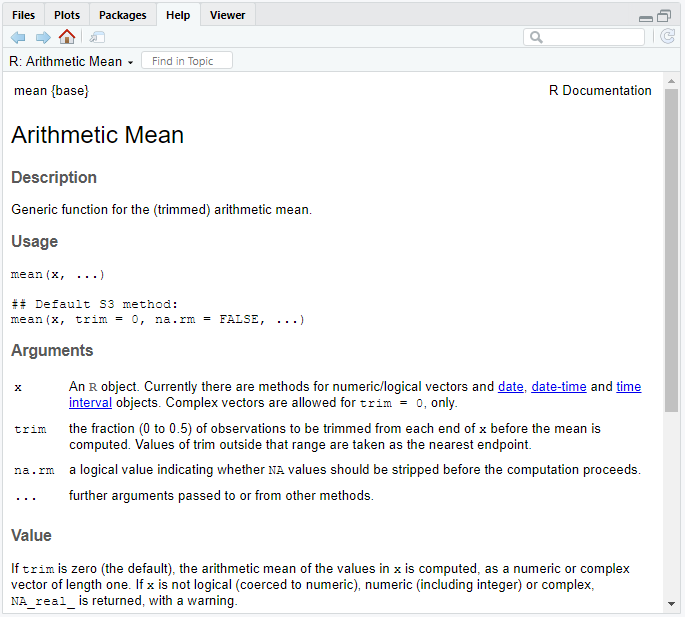

A help page for an R function always has the same basic set-up. Here’s what the first half of the help page for mean() looks like.

At the very top you’ll see the function name, followed by the package the function is in surrounded by curly braces. You can see that mean() is part of the base package.

This is followed by a function title and basic Description of the function. Sometimes this description can be in fairly in depth and useful but often, like here, it’s not and I quickly skim over it.

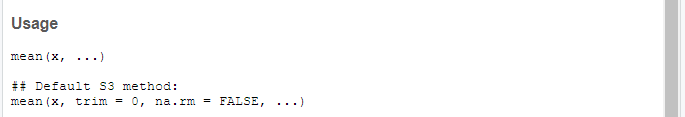

Usage

The Usage section is usually my first stop in a help page. This is where I can see the arguments available in the function along with any default values. The function arguments are labels for the inputs you can give to a function. A default value means that is the value the function will use if you don’t input something else.

For example, for mean() you can see that the first argument is x (no default value), followed by trim that defaults to a value of 0, and then na.rm with a default of FALSE.

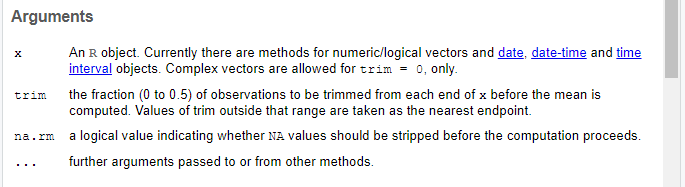

Arguments

The arguments the function takes and a description of those arguments is given in the Arguments section. This is a section I often spend a lot of time in and go back to regularly, figuring out what arguments do and the options available for each argument.

In the mean() example I’m using, this section tells me that the trim argument can take numeric values between 0 and 0.5 in order to trim the dataset prior to calculating the mean. I know from Usage it defaults to 0 but note in this case the default is not explicitly listed in the argument description.

The na.rm argument takes a logical value (i.e., TRUE or FALSE) and controls whether or not NA values are stripped before the function calculates the means. Since it defaults to FALSE, the NA values are not stripped prior to calculation unless I change this.

Examples

If you scroll to the very bottom of a help page you will find the Examples section. This gives examples of how the function works. You can practice using the function by copying and pasting the example and running the code. In RStudio you can also highlight the code and run it directly from the Help pane with Ctrl+Enter (MacOS Cmd+Enter).

After looking at Usage and Arguments I often scroll right down to the Examples section to see an example of the code in use. The Examples section for mean() is pretty sparse, but you’ll find that this section is quite extensive for some functions.

Other sections

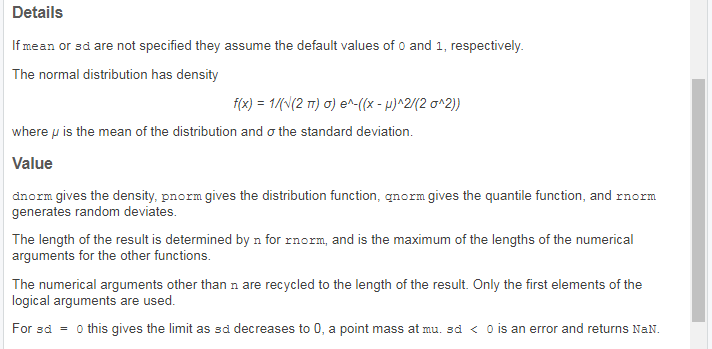

Depending on the function, there can be a variety of different and important information after Arguments and before Examples. You may see mathematical notation that shows what the function does (in Details), a description of what the function returns (in Value), references in support of what the function does (in References), etc. This can be extremely valuable information, but I often don’t read it until I run into trouble using the function or need more information to understand exactly what the function does.

I have a couple examples of useful information I’ve found in these other sections for various functions.

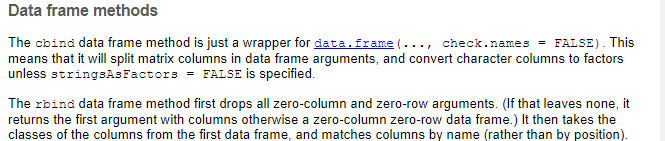

First up is rbind() for stacking datasets. It turns out that rbind() stacks columns based on matching column names and not column positions. This is mentioned in the function documentation, but you have to dive deep into the very long Details section of the help file at ?rbind to find the information.

Second, functions for distributions will give information about the density function used in the Details section. Since the help pages for distributions almost always describe multiple functions at once, you can see what each of the functions return in Value. Here’s an example from ?rnorm.

Using argument order instead of labels

You will see plenty of examples in R where the argument labels are not written out explicitly. This is because we can take advantage of the argument order when writing code in R.

You can see this in the mean() Examples section, for example. You can pass a vector to the first argument of mean() without explicitly writing the x argument label.

vals = c(0:10, 50)

mean(vals)# [1] 8.75In fact, you can pass in values to all the arguments without labels as long as you input them in the order the arguments come into the function. This relies heavily on you remembering the order of the arguments, as listed in Usage.

vals = c(0:10, 50, NA)

mean(vals, 0.1, TRUE)# [1] 5.5You will definitely catch me leaving argument labels off in my own code. These days, though, I try to be more careful and primarily only leave off only the first label. One reason for this is it turns out my future self needs the arguments written out to better understand the code. I’m much more likely to figure out what the mean() code is doing if I put the argument labels back in. I think the code above, without the labels for trim and na.rm, is hard to understand.

Here’s the same code, this time with the argument labels written out. Note the argument order doesn’t matter if the argument labels are used.

vals = c(0:10, 50, NA)

mean(vals, na.rm = TRUE, trim = 0.1)# [1] 5.5Another reason I try to use argument labels is that new R users can get stung leaving off argument labels when they don’t realize how/why it works. 🐝 I worked with an R newbie recently who was getting weird results from a GLM with an offset. It turns out they weren’t using argument labels and so had passed the offset to weights instead of offset. Whoops! Luckily they saw something was weird and I could help get them on the right path. And now they know more about why it can be useful to write out argument labels. 😄

I talk about this issue here because I don’t often see a lot of explicit discussion on why and when argument labels can be left off even though there are a lot of code examples out there that do this. This reminds me of when I was a new beekeeper and I made the mistake of going into a hive in the evening. (Do not try this at home, folks!) It turns out “everyone” who is an expert beekeeper knows what happens if you do this, but it wasn’t mentioned in any of my beginner books and classes. I don’t think beginners shouldn’t have to learn this sort of thing the hard way.

Figure 1: No worries, this is a daytime hive inspection.